Featured Interview with AML Leaders

By Elizabeth Hearst for AMLi

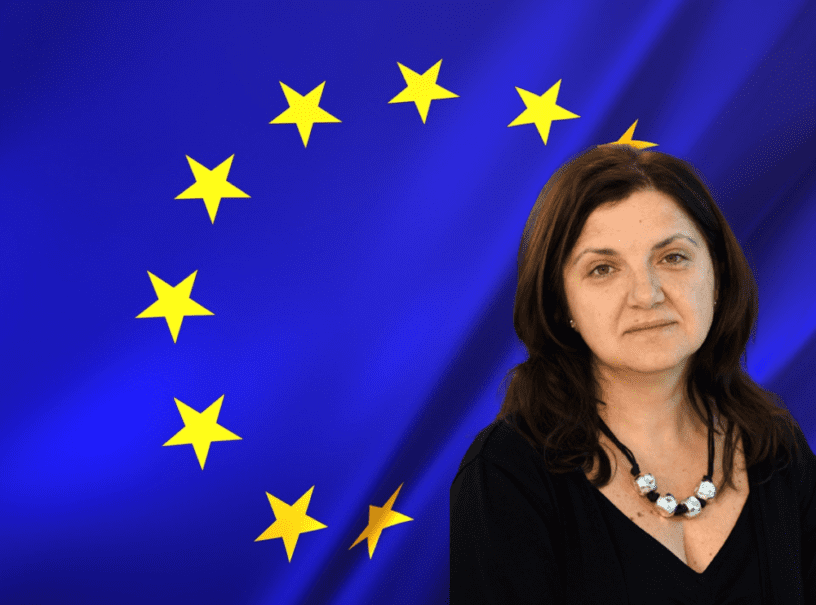

Raluca Pruna is the Head of Unit of Financial Crime in the European Commission. She is eager to crack down on money laundering and financial crime where it exists across Europe. In this exclusive interview with AMLi she discusses the issues Europe faces in the fight against money laundering, how the upcoming sixth money laundering directive will be implemented and closing any existing loopholes to make sure Europe is shut to “dirty money”.

Q. Elizabeth Hearst: This new directive aims to change supervision of AML from a state level to a single EU watchdog, how difficult will this be to implement?

A. Raluca Pruna: On 7 May 2020, the Commission published an ambitious and multifaceted Action Plan, which set out concrete measures that the Commission will take over the next 12 months to better enforce, supervise and coordinate the EU’s rules on combating money laundering and terrorist financing. The aim of this new, comprehensive approach is to shut down any remaining loopholes and remove any weak links in the EU’s rules. Given the many recent case studies –as outlined in a Commission Report on the assessment of recent alleged money laundering cases – that highlighted the weaknesses in the EU’s current anti-money laundering system, an effective and truly deterrent institutional architecture is clearly required. An integrated EU-wide AML supervisory system needs to be established.

At the heart of the new system, it is essential to have a central, independent EU element. This will not, however, replace national supervisors but will oversee and coordinate with them. We are currently also considering whether and how to directly supervise certain entities that present the most significant anti-money laundering (AML) risks.

EH: Currently there are legislative loopholes which vary from country to country, when this directive is enacted, how challenging will it be to close them and tighten up EU-wide security?

RP: The Commission’s Action Plan of 7 May aims to ensure that EU rules are more harmonised and therefore more effective. The rules will be better supervised and there will be better coordination between Member State authorities. Current rules are often ineffective in dealing with new threats arising from innovation, in facilitating legitimate business conducted across borders, or when it comes to ensuring equal supervisory and oversight standards. These facts are by now well established.

The Commission has had ample opportunity to study how the rules are applied across the board, and we have drawn the necessary lessons. Closing these loopholes is going to be challenging, since many issues arise from the existing rules not being interpreted and applied in the correct manner. We are undertaking a very delicate exercise in which we need to preserve all the benefits of the existing legal framework, while also bringing about necessary changes. By clarifying the rules and strengthening them only where necessary – without imposing additional or brand new obligations – we can achieve this goal.

EH: The directive wants to turn parts of the EU anti-money laundering directive into legislation, how can member states enforce this?

RP: The EU framework for AML currently aims to ensure minimum harmonisation amongst the Member States. They are required to transpose the relevant EU rules into their national law. Provisions on Customer Due Diligence, for example, vary across Member States, and even within one Member State. National AML rules can be spread across many legal instruments, making implementation very complicated. Therefore, a key element of the EU’s future framework will be a single rulebook. In practice, this means transforming some parts of the existing AML Directive and enacting it as a directly applicable Regulation.

The Regulation will also aim to include some new clarified and enhanced provisions on certain aspects of the framework, such as Customer Due Diligence. The objective of this single rulebook is to streamline and facilitate the implementation of the framework and to close any “loopholes” which have been identified to date.

EH: It is said that currently there is limited exchange of information between Financial Intelligence Units between member states, what more can be done to ensure cohesion between countries? How important is this in the fight against Money Laundering?

RP: Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) play an essential role in ensuring that the EU’s AML system works. Good communication between FIUs and other relevant authorities is key to effectively fighting against money laundering. Indeed, currently there are still weaknesses in this area. But here again, one could claim that the solution is rather obvious. If coordination is missing, it must be established. Without in any way hindering their current activity, Member State FIUs could be supported through a dedicated EU mechanism that allows them to exchange financial data when required, to have common tools that they can draw on when assessing that data, to look at common issues together, and so on.

Another important element of the Commission’s work is to put the administration of the interconnection between FIUs, known as FIUnet, on a stable footing. Given that for legal reasons it is no longer possible for Europol to host FIUnet, this is an opportunity to establish an EU-level coordination and support mechanism, and enhanced centralised analysis capacity for FIUs. This will significantly improve the overall enforcement capacity within the EU.

EH: Currently, the Anti Money Laundering standards are developed through FATF, what challenges does that bring on an EU level?

RP: The European Commission is a committed and active member of the FATF and plays a central role in the development of its globally applicable standards. The EU legislative framework on AML, the AML Directive and the future single rulebook, apply those standards in EU law – even going beyond them in a number of areas. This process has been running for three decades now, and rather smoothly.

The challenges in respect of the FATF and the Commission’s presence in this standard setting body lie elsewhere. Not all EU Member States are FATF members, and so it is the Commission’s duty to coordinate with all Member States via a dedicated Committee to ensure that all Member States are on board and have a coordinated approach to the FATF standards. This also serves to facilitate implementation of the standards via EU law. However, as announced in the May Action Plan, we are exploring other ways of further coordinating EU positions in the FATF, as it is essential for the EU to speak with one voice in the international arena.

Whatever form the solution will take, particularly regarding the single rulebook, it will have to ensure that the specific nature of the EU, as a supranational body, is better reflected in the FATF framework and that the Union’s own rules can guide FATF’s activity.

EH: There are plans for a radical overhaul of the current regulatory framework to prevent future money-laundering scandals in the EU, how does the EU garner trust in European citizens and institutions after the previous history of scandals?

RP: No jurisdiction in the world is free of money laundering and it is always possible to do better. The EU has already shown its ability to react fast to developments, first of all by rapidly enacting the fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive in 2018, very soon after the fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive of 2015, when it became apparent that the fourth AMLD urgently needed supplementing. Secondly, the EU gave added responsibilities in the ALM field to the European Banking Authority, with effect from the start of 2020. In 2019, the Commission adopted a package of reports on the state of play in money laundering, including a “post-mortem” analysis of the recent high-profile money laundering cases, and a Supranational Risk Assessment. The most recent step was the adoption in May 2020 of an Action Plan, including the commitment to a major legislative package in 2021. There are clearly major money laundering threats in the EU, but in response, actions speak louder than words; that is the background to the present Action Plan.

EH: Can Europe be seen as an international leader in Anti-Money Laundering legislation in the future? What more can be done?

RP: We certainly aim to make sure that the entire world is aware that the EU financial system is closed to dirty money, and that it has the necessary controls in place. Having said that, we remain committed to supporting the role and the work of the international standard setter in this field. From our point of view, the important thing is to have an efficient and well-coordinated international approach to money laundering and terrorist financing via the FATF, rather than the question of who is a leader. Against this background, one of the pillars of the Action Plan is to enhance the international role of the EU in the fight against money laundering. The Commission will play a full role in the FATF strategic review and all other FATF activities. The EU will continue to exercise an autonomous policy towards third countries to protect the EU’s financial system, with the option to impose additional criteria on third countries as compared with the FATF. The methodology published alongside the Action Plan in May this year has enhanced transparency in that regard. At the same time, significant EU technical assistance is available to those third countries that are committed to working to eliminate any identified insufficiencies.

EH: Do you see scope for greater public/private partnerships in the EU to fight AML?

RP: Indeed, exploration of the potential of public/private partnerships (PPPs) is a component of the Action Plan. These partnerships can play a role in making better use of financial intelligence, while respecting data protection requirements. Some existing PPPs are limited to exchanges of information on typologies and trends by FIUs and law enforcement to obliged entities. Others consist of sharing operational information on intelligence suspects by law enforcement authorities to obliged entities for the purposes of monitoring the transactions of these suspects. Supervisors and competent authorities across the EU have sometimes been slow to join or establish such PPPs, be it for legal or practical reasons. And undoubtedly their reluctance was justified in a number of cases. Much depends on the nature of data being exchanged, on the openness of such PPPs or on the need to keep entities that an authority directly supervises at arm’s length. Yet, we are convinced that the global effectiveness of the AML system depends on it being a truly intelligence-led exercise. PPPs can help, and the Commission is expected to issue a guidance on PPPs, in the course of 2021.

EH: What are the greatest weaknesses that have been identified in the current AML regime(s)? How best can these be remedied? Enforcement on a European level is difficult. How do we transcend this difficulty?

RP: In our studies of recent money-laundering cases, we have identified two key weaknesses. First, the level of resources committed to AML investigations and second the communication between relevant authorities. A possible solution to these problems could be an EU-level supervisor with significant resources, and the competence to host a communication network between national supervisors. This would be a very important step towards remedying those weaknesses. At the same time, the single rulebook will considerably facilitate enforcement by harmonising a core set of applicable rules.

EH: FinTech is very important to the EU, how can the new and established players co-operate on AML?

RP: Indeed, FinTech in the area of financial policy is a priority for this Commission. We are currently working on a digital finance strategy, of which one part is a legislative proposal on virtual (or crypto-) asset providers. It is necessary for all relevant players who might potentially be used for money laundering, both incumbents and new fintechs, to be covered by the AML provisions and to therefore be “obliged entities” under the legislation. This will create an obligation to cooperate with FIUs and to be supervised appropriately. Careful attention will therefore be paid to the definition and scope of Fintech obliged entities in next year’s legislation. The Commission will coordinate internally to ensure coordination between the different policy initiatives, in order to ensure that overlaps and underlaps will be avoided.

EH: What role do you see specialised publications such as AMLintelligence.com playing in the fight against AML?

RP: Transparency, awareness, activism and openness towards obliged entities, experts, civil society and citizens at large are the cornerstones of the EU’s AML system. Just take a look at how much emphasis the legal framework places today on the role of journalists, mentioned so frequently in the AML Directive, and the need to make beneficial ownership information as accessible as possible. Publications such as AMLintelligence play an essential role. We certainly appreciate the efforts put into clarifying the rules for experts and citizens alike, raising attention and pointing to issues most commonly arising in the application of the rules. Let me add that Commission experts are themselves avid readers. It is very important to have a good overview of what is happening daily, putting on our radar emerging risk areas. Areas such as sports, gambling, free ports and so on, have all emerged as risk areas in recent years, and the technology sector is in constant evolution, leading to new risks. In addition, individual cases can be important insofar as they highlight deficiencies in enforcement, which allowed them to remain undetected for a certain time. Publications such as yours can play a vital role in disseminating information on these areas.

Share this article:

Follow us: