MONEY LAUNDERING and terrorist financing are specifically covered in the Brexit Treaty between the EU and Britain.

While relations between the bloc and the UK will never be the same and co-operation on AML matters will be elongated and by necessity more complex, they are specifically covered by Title X on page 363 of the Treaty. The agreement covers the exchange of information between competent AML authorities in the EU and UK.

“The EU-UK agreement provides for cooperation on combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism. It does so by confirming the EU and UK’s continued commitment to Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards,” a Commission official told AML Intelligence.

“Beyond that, it sets out arrangements to ensure the transparency of beneficial ownership for companies and trusts and the exchange of such information between competent authorities [FIUs and statutory agencies],” the spokesperson added.

From January 1 Britain is operating its own AML regime, covered by the UK’s Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (the Sanctions Act).

While closely aligned with the current EU sanctions and money laundering legislation, it is unclear how long Britain will decide to stay in tune with Europe’s regulations or to continue to replicate EU sanctions lists – although it will comply with UN sanctions lists.

Further divergence between the EU and Britain however will undoubtedly occur early 2021 when the European Commission publishes its adoption plans for a comprehensive Union policy on preventing money laundering and terrorism financing.

Financial Services Commissioner Mairead McGuinness will within weeks announce how a single money laundering rule book will be applied across the bloc. Critically she will also decide who the single supervisor in the EU will be – a standalone agency or an entity within the European Banking Authority. Quite clearly Britain will be outside this process and it will be up to the British parliament how far it will co-operate with the new European supervisor.

‘The treaty sets out arrangements to ensure the transparency of beneficial ownership for companies and trusts and the exchange of such information between competent authorities’

Of course, financial services per se remain outside the terms of the Brexit Trade Deal and critically the relationship between the EU and Britain in this most important services area has yet to be decided.

While not as mammoth in scale as the overall treaty it will be just as tricky to negotiate and EU Member States are likely to be less anxious this time round to strike a deal that is as favourable to London. Indeed in many European capitals there is a feeling London as a financial capital benefitted heavily from EU membership and now that Britain has left the bloc that is must feel some pain in this area.

“Some well known leaders in European capitals believe Britain should be delivered a bloody nose in the financial services area. The UK has come out of the Brexit process pretty good overall but why should it benefit from financial services to such an extent that it would weaken financial services in the EU, possibly leading to a flight back of companies from Europe to London. The Brexit Treaty, covering 1,200 pages, may be done but it does not cover financial services and this will be a very difficult area in which to reach agreement,” one senior EU official told AML Intelligence.

While it is undoubtedly good news that AML and CFT are covered in the treaty, clearly the resilience of the agreement in this area will be tested down the months and years to come, particularly as the treaty does not yet cover financial services per se.

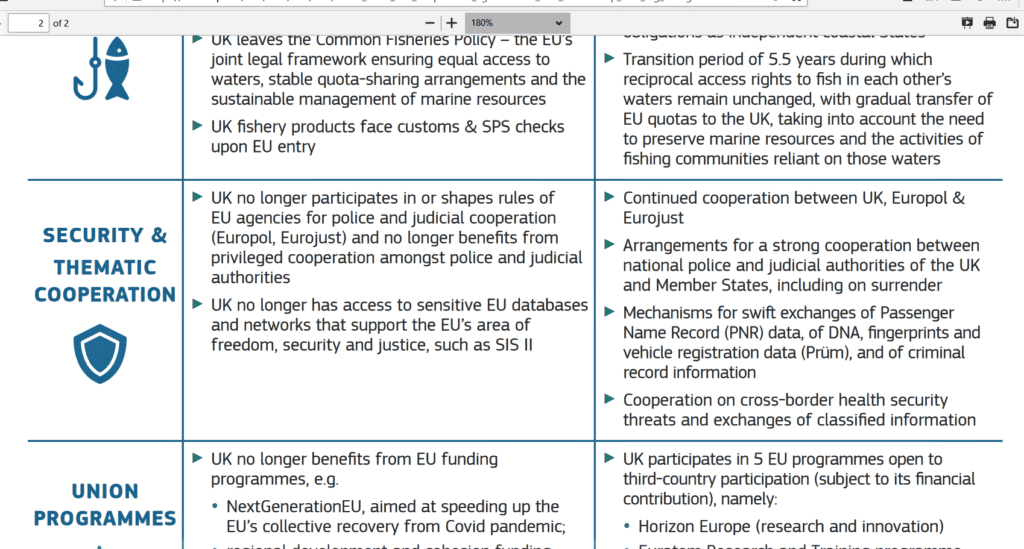

Britain will be out of Europol and Eurojust which is a blow to law enforcement across the continent. While the UK can send delegations – effectively observers – to both institutions and co-operation and information flow will continue, Britain will not have any input into decision making at both agencies. At Europol British officers have traditionally held senior positions and even led the organisation. The Brexit deal however does mean co-operation between EU and British law enforcement agencies can continue – albeit in a less joined up way.

Here are the highlights of the treaty, regarding financial services, AML/CFT and cybersecurity:

FINANCIAL SERVICES

Financial services have always been the most fraught of sectors in the Brexit talks – particularly as Britain has signalled openly that it wants to compete fiercely with the EU here.

It’s hardly a surprise then that the sides have not reached an agreement and have set a March 2021 deadline for a deal – but like the Brexit talks themselves don’t hold your breath.

European capitals fear a massive landgrab by London and a nightmare scenario would be banks and financial services companies departing Paris, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Luxembourg, Copenhagen and Dublin moving to London. Therefore this will be a very thorny issue and it is likely the EU will not want Britain to receive as favourable terms as it has in the overall treaty.

‘Britain will begin its new relationship with the EU on January 1 with fewer equivalence rights than financial capitals such as New York and Singapore – and the UK will have to rely on more cumbersome and limited access arrangements’

The UK still has much to lose and the EU to gain. More than 90% of euro-denominated interest-rate derivatives and 84% of foreign-exchange trading in the EU take place in Britain, according to New Financial.

Right now Britain will begin its new relationship with the EU on January 1 with fewer equivalence rights than financial capitals such as New York and Singapore – and the UK will have to rely on more cumbersome and limited access arrangements.

For now the EU and Britain aim to agree by March 2021 a Memorandum of Understanding establishing a framework for regulatory cooperation on financial services.

British prime minister Boris Johnson admitted the Brexit trade deal failed to meet his ambitions on financial services. The EU has signalled that the City of London must wait until after January 1 to learn what market access it will have in future.

That’s hardly surprising as Mr Johnson said Britain would use its new regulatory freedom to diverge from the EU’s rules, particularly on financial services. The British premier told the Brexiteer cheerleader Sunday Telegraph the treaty “perhaps does not go as far as we would like” on financial services.

Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak has said in characteristic UK understatement that Britain wants to “do things a bit differently” on financial services after departing the single market but remains hopeful both parties would work together. “This deal also provides reassurance because there’s a stable regulatory co-operative framework mentioned in the deal,” he told journalists. “I think that will give people that reassurance that we will remain in close dialogue with our European partners when it comes to things like equivalence decisions.”

The Commission and Member States made clear the UK must wait to learn what market access rights its financial services companies will have in future, warning that they will hinge on how far Britain diverges from EU standards.

The EU and UK have agreed that decisions on access to markets in financial services will be based on each side declaring unilaterally that the other side’s regulatory systems are “equivalent” to its own.

The equivalence system — which Brussels already uses with other non-EU financial centres — does not cover all financial services and allows access rights to be withdrawn at just 30-days’ notice.

London’s financial markets prospered in the last four decades as the UK capital became the pre-eminent EU hub for lending, trading and investing.

Now outside the EU, the future size and influence of the city’s finance industry is in question. The financial services sector has the biggest trade surplus of any industry in the U.K., with exports in 2019 of £79 billion, equivalent to $106 billion.

According to a European Commission statement: “Both sides commit to ensuring that internationally agreed standards in the financial services sector are implemented and applied in their territories. Both parties preserve their right to adopt or maintain measures for prudential reasons (‘prudential carve-out’), including in order to preserve financial stability and the integrity of financial markets.”

MONEY LAUNDERING

The Brexit Treaty explicitly provides for cooperation on combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism. “It does so by confirming the EU and UK’s continued commitment to Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards,” the European Commission told AML Intelligence.

“Beyond that, it sets out arrangements to ensure the transparency of beneficial ownership for companies and trusts and the exchange of such information between competent authorities,” the Commission adds.

The part of the treaty covering AML/CFT is: TITLE X: ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING AND COUNTER TERRORIST FINANCING, Article LAW.AML.127. It provides:

- The Parties agree to support international efforts to prevent and combat money laundering and terrorist financing. The Parties recognise the need to cooperate in preventing the use of their financial systems to launder the proceeds of all criminal activity, including drug trafficking and corruption, and to combat terrorist financing.

- The Parties shall exchange relevant information, as appropriate within their respective legal frameworks.

- The Parties shall each maintain a comprehensive regime to combat money laundering and terrorist financing, and regularly review the need to enhance that regime, taking account of the principles and objectives of the Financial Action Task Force Recommendations

The article defines beneficial and ultimate beneficial owners and also describes FIUs as the competent authorities in each country or Member State.

According to the article: “Each Party shall establish or maintain a central register holding adequate, up-to-date and accurate information about beneficial owners. In the case of the Union, the central registers shall be set up at the level of the Member States. This obligation shall not apply in respect of legal entities listed on a stock exchange that are subject to disclosure requirements regarding an adequate level of transparency. Where no beneficial owner is identified in respect of an entity, the register shall hold alternative information, such as a statement that no beneficial owner has been identified or details of the natural person or persons who hold the position of senior managing official in the legal entity.”

From January 1, Britain is no longer subject to EU sanctions. The UK’s fincrime regulations will come under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (the Sanctions Act) which was enacted with Brexit foremost in mind by Westminster.

The Act covers the comprehensive list of persons, bodies or marine craft designated under sanctions regimes that companies are restricted from dealing with. These are drawn the lists the UK has chosen to carry over from the EU regimes and those it obliged to implement under UN regimes.

In Britain, sanctions violations have been on the rise. According to the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation there were a record 140 voluntary disclosures of potential sanctions violations related to transactions worth a total of £982 million between April 2019 and March 2020. In the same period between 2018 and 2019 there were 99 reports related to transactions worth a total of £262 million.

“The voluntary disclosures came mainly from the banking and financial sectors and on 31st March 2020 the OFSI announced it had imposed a £20.47 million fine on Standard Chartered Bank,” according to Dr Richard Jeffries.

Writing in Global Banking & Finance Review, he noted: “The bank issued over 100 loans to Denizbank A.S between April 2015 and January 2018. At this time, the Denizbank was wholly owned by Sberbank in Russia, which was under the Ukraine Sanctions regulations. The fine marked a significant shift in the OFSI’s approach, with the highest fine up till that point a comparatively meagre £140,000. Other sectors making voluntary disclosures are insurance, charity, travel and legal.”

LAW ENFORCEMENT

A no-deal Brexit would have been the Doomsday scenario for law enforcement co-operation between the EU and Britain.

Without an Agreement, cooperation between the EU and the UK would have relied on international cooperation mechanisms only (such as Interpol and the relevant Council of Europe Conventions). The UK would not have been able to benefit from a cooperation framework with EU law enforcement agencies such as Europol and Eurojust.

Nonetheless, it is not a good scenario for European law enforcement. Instead of having institutional relationships the EU/UK will revert back to relying on inter-personal and network relationships in the policing and judicial spaces (a big ask in a union of 27 states). Britain will enjoy only observer status in Europol and Eurojust and will not get access to the SIS2 criminal intelligence database – a vital and practical tool in day-to-day policing.

However, both sides have agreed to establish a new framework for law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, allowing for strong cooperation between national police and judicial authorities, including ambitious extradition arrangements, and the swift exchange of vital data.

‘Provisions on Europol and Eurojust would enable the UK to take part in common operations, in investigation teams and in analysis projects on specific crime areas such as drug trafficking or terrorism’

The treaty also includes a commitment by the EU and UK to uphold high levels of data protection standards. In principle, where personal data are transferred, the transferring Party shall respect its rules on international transfers of personal data.

“For law enforcement and judicial cooperation, high levels of data protection standards are essential. These are to be ascertained by adequacy decisions taken unilaterally by each side,” the European Commission said.

” On the EU side, this means decisions attesting that UK standards are essentially equivalent to the EU standards set out in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Law Enforcement Directive, and that they respect specific additional data protection standards stemming from opinions of the EU Court of Justice,” the Commission says.

As a third country, the UK will no longer participate as a full member of Europol or in the judicial cooperation agency Eurojust. As such it will no longer have a say in the decisions of those agencies.

Nonetheless, the draft EU-UK agreement will enable effective cooperation between the United Kingdom and Europol and Eurojust, in line with the rules for third countries established in EU legislation.

This is designed to “help ensure robust capabilities in tackling serious cross-border crime”. In practice, provisions on Europol and Eurojust will allow the UK to take part in common operations, in investigation teams and in analysis projects on specific crime areas such as drug trafficking or terrorism. Britain will also be allowed get analytical support from Europol, use common secure communication channels, second Liaison Officers to Europol and a Liaison Prosecutor to Eurojust, share data and be informed about relevant data concerning the UK.

However, the UK will not have access to the Europol Information System nor full access to Eurojust’s case management system, nor have any role in the governance of the two EU agencies. This is bound to have a serious effect on day-to-day policing operations.

In the House of Commons former British Prime Minister Theresa May bemoaned that the UK will no longer has access to the SIS2 (Schengen Information Service 2) database. This is an important which contains data from all Member States and some third countries who are Schengen area members. Intelligence is inputted by members on wanted terror and crime suspects as well as more practically missing persons, stolen or missing passports and stolen property. There were 91 million alerts on SIS2 accessed 6.6 billion times (UK was third highest user) during 2019. Clearly this sharing of critical real time data will negatively disrupt international criminal inquiries and practical policing.

It is certainly an area that will have to be revisited once the post-deal period has bedded in and the impact of the move is analysed in full.

CYBERSECURITY

Given that most fincrime is now occurring online, it was important that the Brexit Deal cover cybersecurity.

Cybersecurity threats are often cross-border in nature, and are estimated to cost the global economy €400 billion every year. These attacks can affect our security, prosperity and democratic order.

Faced with increasing cybersecurity challenges, EU Member States co-operation is at a nascent stage and the agreement allows Britain to be part of new initiatives.

Britain’s National Cyber Security Centre is one of the leading agencies of its type in the world, while the EU is trying to develop the reputation of Enisa as a super-EU cyber agency.

Here is an area that is ripe for cyber criminals to exploit variances in jurisdictional enforcement that already facilitate money lauderers.

For now the Agreement sets out a number of initiatives between the EU and the UK including a regular dialogue on cybersecurity, and cooperative actions at international level to strengthen global and third countries’ cyber-resilience.

Both sides have also agreed to exchange best practices and actions aimed at promoting and protecting an open, free, and secure cyberspace.

Subject to an invitation by the relevant EU authorities, these actions include the possibility for the UK, to:

- cooperate with the EU Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-EU) to exchange information on cyber-related tools and methods;

- participate in activities conducted by the Cooperation Group established by Directive (EU) 2016/1148, related to capacity building, security-related exercises, risk and incident-related best practices, awareness raising, education and training, and research and development;

- participate in certain activities of the EU Cybersecurity Agency (ENISA) related to capacity building, knowledge and information, and awareness-raising and education.