By Stephen Rae for AML Intelligence

AS A YOUNG district court reporter in Dublin in the late 1980s the lines of defendants were an eye-opener. Primarily heroin addicts charged with assortments of crime from burglaries to car thefts and violence, occasionally there were professional thieves, every so often a gangland boss or IRA terrorist suspect. And then there were the fraudsters (back then it was singularly cheque book fraud). Invariably looking like successful bankers, dressed in smart suits, spoke well and carrying an air of bemusement as to why they were in court at all. Most of all they were convincing; in the witness box their narrative was almost compelling.

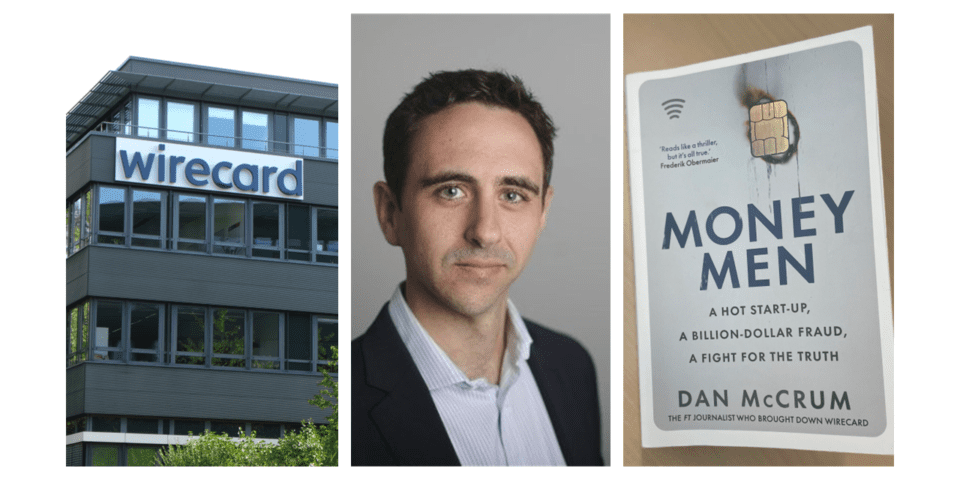

‘Money Men,’ the authoritative account of the international deception that was Wirecard, is full of these characters, living lives of uproarious luxury in Munich, Vienna, Singapore, Dubai, Manila – and even Tripoli.

Chief amongst them is Jan Marsalek, Wirecard’s COO who has previously been portrayed as a fantasist but who we find out is really the ultimate conman, aided by a cast of fellow fraud masterminds and dubious ex-military and secret service enablers. He comes across as having the illusory tricks of a magician.

Author Dan McCrum – who assiduously chased the Wirecard story for the Financial Times – describes the fintech COO’s nature. “Marsalek’s hero in business was Dietrich Mateschitz, the Austrian marketing genius who had launched Red Bull in Europe in 1987. What really caught Marsalek’s imagination was the intangible nature of it all. The business was worth billion, he said, but from the very first minute everything was outsourced, the production, the distribution. ‘Behind the brand is nothing but air. Isn’t that brilliant?’ he enthused.”

Marsalek, with his love of the high life, nightclubs and incessant travel (he claimed to fly more miles that the average cabin crews) is given the space to build out Wirecard’s deception of its shareholders, workers and board by CEO Markus Braun who rallies staff with lines like: “You know we are not going one mile, we are going two miles, we are going the extra mile.” Tell me that’s not a warning sign in a CEO!

To investors, the German authorities and many rivals, Wirecard’s success as payments processor is through its canny international acquisitions.

But McCrum explains Marsalek’s modus operandi: “Imagine the auditor opens the treasure chest and finds it empty. We spent the gold on that building at the top of the hill, you say, handing them a telescope. So long as the accountant doesn’t walk up there and discover the house is just a wooden façade (or indeed get on a flight to Bahrain) everything is fine.” Which of course auditors EY ably assisted Marsalek and co in doing so by failing to getting on those flights to far-off destinations to check the validity of the acquisitions.

McCrum’s journalistic source Leo Perry describes how the illusion works. “Faking profits you end up with a problem of fake cash. At the end of the year the auditor will expect to see a healthy bank balance, it’s the first thing they check. So what you have to do is spend that fake cash on fake assets.”

Of course Germany’s reputation for technocratic good business also helped Wirecard’s reputation against countries, say like, China.

“Germany was different,” writes McCrum. “It was the well adjusted, highly educated manufacturing heart of Europe. Its coalition politics, tortuous to the outsiders, suggested a robust institutional weight. Its record of consensus-building extended to business, with the unions and executives engaged in grand projects for prosperity. Germans’ soer culture of thrift was renowned and thanks to the European debt crisis German government debt securities – known as Bunds – were about the safest asset going. If an international investors gave any thought at all, they would probably have ranked German institutions among the best in the world. There were many Teutonic stereotypes available, but incompetent crooks wasn’t one of them.”

All of which played into the unscrupulous hands of Wirecard’s criminal leadership.

When KPMG were called into investigate the sham that was Wirecard, the façade began to collapse slowly and then suddenly. Marsalek was asked by the auditors where the company’s €1.9 Billion was on deposit. He replied: “Give me a little time to figure, I forget the name.” Incredibly he’d also forgotten the country, it was either Russia or the UAE, he said – eventually a few days later saying it was in Manila! Still the cops weren’t called in.

The author comes into his own with some great descriptions of the individuals. Off to the Phillipines where the auditors meet Wirecard’s man on the ground. “The German payments executive looked like an Asian sex tourist. He was over six feet tall, missing teeth, with a belly hanging over black jeans and a matching sweatshirt which showed his dandruff,” we’re told.

KPMG would eventually report the truth that lay in clear sight all along. Wirecard’s core European payment processing operations made no profit at all. All of the so-called fintech’s Ebitda came from commissions at its Dubai, Singapore and Manila centres which were total frauds.

Still the incompetent and stuffed Wirecard board dithered once more – until it had no choice and the whole charade came tumbling down.

By then €870M had been looted from the company via loans to its opaque global partners. It would cost the careers of many, not least the head of laissez faire German watchdog BaFin and his second-in-command.

This is a story well told by McCrum and riveting right to the end.

The characters are suitable of le Carré, from Russian GRU agents to Libyan spymasters – and a not inconsiderable number of nightclub owners cast as whisteblowers and double agents.

There is also the underlying story of journalistic tenacity which is the spine of the narrative as the author and his investigations editor Paul Murphy show resilience in the face of uber-threatening legal letters from big name firms and the dark arts of well paid PR enablers.

This is an amazing fincrime book but it also an extraordinary journalistic book. All reporter’s will be smile at the passages around green ink letters, meeting contacts in discreet restaurants and coffee shops – and the fear that comes in the face of corporates employing ex-spies and coming up against the bureaucratic indifference of so-called watchdogs.

McCrum rightly casts editor Lionel Barber in a strong light for his courage in the face of an aggressive onslaught by Wirecard and its enablers (certainly the tome is better written than Barber’s own indulgent memoirs).

There are also the magnificent heroes of the tale such as the Singapore based lawyer Pav Gill and his brilliant mother whose endeavours would eventually lead to Wirecard’s collapse.

AML professionals will read with horror the company’s complete lack of compliance protocols. A McKinsey report found: “If anyone was doing the anti-money laundering checks required by law on the money gushing through the systems of these third parties, it wasn’t Wirecard.”

There’s also a nugget around board incompetence in the face of the lack of AML processes: “The board appeared to be paying attention although the lawyer noticed that Anastassia Lauterbach and Thomas Eichelmann seemed to detest each other, vying for prominence and the last word.”

As many Germans swelter under the Majorcan sunshine this month, partying to schlager songs some of which poke fun at the Brits, they may ponder how the English may have saved Germany’s financial system!

‘Money Men’ reveals how Marsalek’s PR advisor (on a mere €850 per hour) came up with the idea of the fintech taking over Deutsche Bank. The plan codenamed “Project Louis XIII” came shockingly close – and of course if it had the PR man would have received a multi-million euro commission.

Thankfully Wirecard collapsed before it could consume Deutsche – and in doing so hiding forever all its dirty secrets within the machinations of the banking giant.

If it wasn’t for the inquiring UK reporters on the FT – who incidentally were hammered for their stories by the German financial press (Suddeutsche Zeitung the notable exception) – the takeover could well have happened! And that would be an entirely different story.

All round a captivating narrative that is scarily true of a fintech that was too big to fail, of regulators, authorities and investors who desperately wanted a German tech success story and who were too easily willing to turn a blind eye to the audacious fraud in plain sight.

Share this on:

Follow us on: