By Sarah Beth Felix

Our Special Correspondent

According to US agencies FinCEN and the IRS today (Tues), there are hundreds of millions of dollars lost every year to these types of schemes which mainly use US financial institutions and MSBs.

Their joint Notice outlines various ways in which these individuals perpetrate tax and workers compensation insurance fraud, typically involving two schemes and provides red flags for institutions.

The first scheme, which is insurance fraud, does not have a ‘financial component’ in terms of red flags that a financial institution can detect. Most community institutions (banks and credit unions) will not be privy to the 4 steps outlined in Figure 1, below.

Even during an EDD or high-risk customer review, I’m not aware of any guidance or suggestion for analysts to review workers’ compensation information on state websites and compare against the volume of payments in/out of the account. That data availability would vary by state and it would add yet another data piece that requires a human to go get the information, which of course adds minutes to an already time-heavy task of high-risk customer reviews.

It seems that the initial red flag for the insurance fraud (part 1) scheme would be the establishment of a shell company, which is a nebulous term for bankers. A shell company doesn’t look like a shell company on day 1 of account opening; and even over time it is highly dependent on a human to analyze various contextual factors to determine if a company is a shell company.

Unravelling what shell companies look like from transactional data and open-source information is for another time. Once the shell company is established, part two of the scheme (tax evasion) can take place. And from the looks of it, this part of the scheme is the most lucrative for illicit actors.

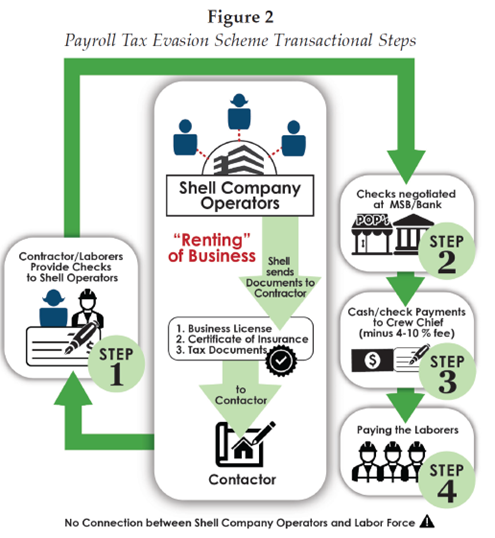

Tax evasion (payroll), while not mentioned in FinCEN’s National Priorities published June 30, 2021, is the main focus of this Notice. As noted in Figure 2 (below), the main parts that are applicable to and detectable for financial institutions are the following: shell companies, checks, cash, and cashed checks.

For most community institutions, branch personnel know business owners that come in and cash checks to then pay their employees. While that may be a smaller dollar amount, and most likely doesn’t involve shell companies, it is still considered a red flag according to this Notice.

Several of these red flags can be operationalized because they deal with data that exists already within the institution and can be retrieved fairly easily. However, some red flags like #2, #3, and #4 require information that is not bank-data-friendly. For example, #2 states – “The person or company opening the account has no known prior involvement with, or in, the construction industry”.

Other than looking up someone’s LinkedIn for every new account, how would an institution know this? Another example is #3 which states – “Beneficial owners of the shell company…may have prior convictions for fraud”. I’m not aware of any new account opening process for checking accounts that looks at a UBOs criminal history.

FinCEN, IRS-CI and HSI identified 11 red flags that could indicate involvement in the two schemes outlined. The Notice states – “No single red flag is determinative of suspicious activity, and financial institutions should consider the surrounding facts and circumstances…” I would respectfully adjust that statement for community institutions. Most of these red flags should be enough to start an investigation, even if it ends in a no SAR filed.

There are takeaways for financial institutions when reading this Notice –

1) Add construction companies to the ever-expanding higher risk NAICS list. However, make sure that there are other transactional components as part of the flagging process… cashed checks, non-US passport UBO or account signer, etc.

2) When researching companies online (should be step 1 in investigative practices) and there is no web presence (a website, google reviews, etc.), ask yourself how this company makes this much money if they can’t be found online. That is usually the easiest indicator of a shell company. High revenue with no web presence is unreasonable.

3) When payments are flowing to a company from other related trades, research the owners and agents of those other companies to determine if they are related (most times they are).

4) During analysis of revenue and expenses for construction companies, if there are no ACH descriptions indicating IRS or state taxes, even though the revenue would justify tax payments, that may be an indicator of evasion. The company could pay the IRS via check, so look for higher dollar checks that are recurring.

5) Send a bulletin to branch staff that if they become aware of customer’s making statements that the checks being cashed or cash withdrawals are for payroll, then it should be sent via the prescribed method for internal SAR referrals.

6) Running analytics based on IP address matching, with differing EINs and related NAICS codes would be a fantastic way to operationalize red flag #10.

Overall, receiving detailed Notices from FinCEN and partner agencies is exactly what financial institutions need. But it can’t just be read by AML Officers and not operationalized. There is always something that can be done to evaluate an institution’s exposure to the schemes explained in this and other Notices.

- The author Sarah Beth Felix has over 20 years of experience in AFC with operational, audit and consulting roles. Through her years as a Chief AML Officer, she provides highly operational and effective solutions in remediation projects, system validations, audits, and operational strategy. Working with both traditional institutions and FinTechs, she is an expert in distilling FATF, Wolfsberg, Egmont, FinCEN and other global guidance into actionable and effective risk-based programs. Palmera Consulting is her advisory firm serving global clients since 2011. She is also co-founder and CAMLO for a new digital correspondent bank, Acceleron Bank, in formation and based in Vermont.