By Vadim Kleiner

Director of Research, Hermitage Capital Management

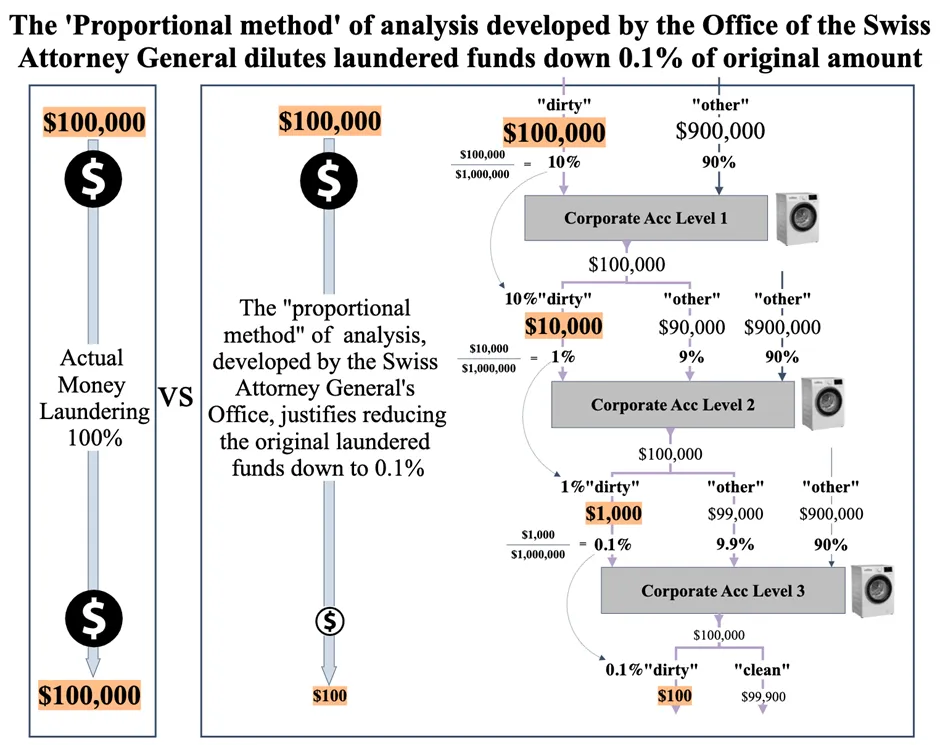

How the Swiss Attorney General Office introduced a mechanism awarding sophisticated money launderers and how the Federal Criminal Court in Bellinzona turned it into legal precedent.

Over the past fifteen years, notable investigations and exposés, such as the Magnitsky Investigation, Laundromats, Offshoreleaks, Panama Papers, and Pandora Papers, have shed light on the staggering scale of global money laundering with trillions of dollars, predominantly originating from kleptocracies like Russia and other former USSR countries. These illicit funds are cleverly disguised and anonymized through laundering mechanisms, infiltrating the Western financial systems via a vast network of banks, lawyers, real estate agents, and have been utilized to purchase influence, garner political support, and secure positions within local establishments.

Recently there have been efforts to combat money laundering such as the Prevezon Case in the US, notable for its lawyer’s meeting with Donald Trump Jr., and Danske Bank’s guilty plea for laundering $160 billion through US banks. The most notorious money laundering banks in Cyprus, Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania have been closed and major banks, including Santander, Wachovia, Standard Chartered, HSBC, and Goldman Sachs, have faced penalties for their involvement in money laundering[1].

While significant progress has been made in combating money laundering in various countries, Switzerland is moving in the opposite direction. In the summer of 2021, the Swiss Attorney General’s Office (SAG) announced the closure of the Magnistky money laundering case, which was opened in response to the complaint filed by Hermitage Capitals in 2011. The SAG confirmed the accuracy of Hermitage’s analysis of the flow of illicit funds. They discovered that the criminal proceeds from a $230 million fraud were found in a Swiss account belonging to the then-husband of Olga Stepanova, a Russian tax official who had approved an illegal tax refund and the accounts of Denis Katsyv, the son of a Russian government official and owner of Prevezon Holding, who settled similar charges with the US Department of Justice in 2017 by paying $6 million.

Swiss prosecutors decided to seize CHF 4 million but chose to release the remaining frozen CHF 16 million. This raises the question of how such a decision was reached.

Money laundering is a sophisticated white-collar crime, involving the passage of illicit funds through multiple shell company accounts. Each additional layer of transactions serves to further obscure the origin of the criminal money. Criminals often intermingle the proceeds from one illegal activity with funds obtained through other criminal activities, making it increasingly challenging for authorities to unravel the illicit activities and hold the perpetrators accountable.

In this case, the SAG collected substantial evidence, allowing them to reconstruct the trajectory of illicit funds. However, the SAG decided to utilize the “proportional method” for analysing the amount of laundered funds at each level of the money laundering scheme which has never been used like that before.

According to the SAG’s logic, if $1 million enters the first level of the money laundering process, and $100,000 of this is clearly of criminal origin, while the remaining $900,000 is from an unidentified source, then every dollar that leaves this account should be treated in the same proportion. In essence, the SAG will only perceive the total amount in the account, as 10% ‘dirty’.

Continuing this, in the second level of the money laundering process, the criminal would then mix the $100,000 of dirty money, with $900,000 with funds from an unknown origin. Under the SAG’s logic, they would only consider $10,000 that left the first level as dirty, or 1% of the incoming $1 million to the second level, and the remaining $990k (99%) as clean.

This ratio the SAG then applies to the funds leaving the second level. When $100k leaves the second layer of money laundering, only 1% of them or $1k is considered dirty by SAG, and the remaining $99k are perfectly clean.

After the same approach applied on the third level of money laundering, the original dirty $100,000 are discounted down to $100 only, or 0.1% of original criminal funds.

It is obvious to anyone familiar with money laundering investigations that the analytical method employed by the SAG has little connection to reality. The use of multiple layers in money laundering schemes is precisely intended to obscure the origin of the funds, not to make them disappear in the process of laundering like the SAG’s method implies.

The SAG’s application of the “proportional” approach in the Magnitsky investigation led them to conclude that only 25% of the frozen funds should be confiscated.

Moreover, the Swiss Federal Criminal Court fully endorses the SAG’s “proportional” approach. The court justifies this stating that the proportionality solution ensures a balanced outcome that does not favour either party[2]. The court also approved the SAG’s calculations based on this method[3], establishing it as a legal precedent.

The proportional method introduced by the SAG has undoubtedly damaged Switzerland’s reputation. However, the more concerning consequence is that it has effectively opened Pandora’s box. Now, any money launderer wishing to launder hundreds of millions or even billions through the Swiss financial system who gets caught by authorities, can simply request the application of this proportional method as a legal precedent. By paying a small fee determined by the SAG using this method, they would be able to retain 99% of the laundered funds, essentially legitimizing and benefiting from their illicit activities. This situation seriously compromises the integrity of the Swiss financial system and its ability to combat money laundering effectively.

It is crucial for other countries to be fully aware of the deficiency that has been incorporated into the Swiss legal framework. It presents an opportunity for money laundering on a mass scale. Therefore, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) should consider putting Switzerland on a “blacklist” of High-Risk Jurisdictions subject to a Call for Action[4] and Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index.

The rating agencies: S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch need also to make immediate steps to reflect this major failure of Swiss AML framework, while evaluating Swiss financial institutions. In addition to that Government’s around the world should reconsider their relationship with Switzerland, as the country no longer meets the approved standards for combating money laundering.

Notes:

– All numbers provided in the example are hypothetical and used to illustrate the method employed by the SAG.

References:

[1] https://credas.com/resources/the-biggest-banking-aml-fines/

[2] https://bstger2.weblaw.ch/cache?guiLanguage=de&q=BB_2021_198&id=57ac5b14-e35f-469c-b029-a35f74ac4aa6&sort-field=relevance&sort-direction=relevance

[3] https://bstger2.weblaw.ch/cache?guiLanguage=de&q=BB_2021_193&id=30e01c77-5f42-4a98-bcbc-3090cd8f4d8b&sort-field=relevance&sort-direction=relevance

[4] https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/countries/black-and-grey-lists.html

Share this on:

Follow us on: